International Brigades

The International Brigades (Spanish: Brigadas Internacionales) were military units made up of anti-fascist volunteers from different countries, who traveled to Spain to defend the Second Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939.

An estimated 32,000[1] people from a "claimed 53 nations"[1] volunteered. They fought against rebel Spanish Nationalist forces, who were led by General Francisco Franco and assisted by German and Italian forces.

Contents |

Formation and recruitment

Using foreign Communist Parties to recruit volunteers for Spain was first proposed in the Soviet Union in September 1936—apparently at the suggestion of Maurice Thorez[2]—by Willi Münzenberg, chief of Comintern propaganda for Western Europe. As a security measure, non-Communist volunteers would first be interviewed by an NKVD agent.

By the end of September, the Italian and French Communist Parties had decided to set up a column. Luigi Longo, ex-leader of the Italian Communist Youth, was charged to make the necessary arrangements with the Spanish government. The Soviet Ministry of Defense also helped, since they had experience of dealing with corps of international volunteers during the Russian Civil War. The idea was initially opposed by Largo Caballero, but after the first setbacks of the war, he changed his mind, and finally agreed to the operation on 22 October. However, the Soviet Union did not withdraw from the Non-Intervention Committee, probably to avoid diplomatic conflict with France and the United Kingdom.

The main recruitment centre was in Paris, under the supervision of Polish communist colonel Karol "Walter" Świerczewski. On 17 October 1936, an open letter by Joseph Stalin to José Díaz was published in Mundo Obrero, arguing that liberation for Spain was a matter not only for Spaniards, but also for the whole of "progressive humanity"; in a matter of days, support organisations for the Spanish Republic were founded in most countries, all more or less controlled by the Comintern.

Entry to Spain was arranged for volunteers: for instance, a Yugoslavian, Josip Broz, who would became famous as Marshal Josip Broz Tito, was in Paris to provide assistance, money and passports for volunteers from Eastern Europe. Volunteers were sent by train or ship from France to Spain, and sent to the base at Albacete. However, many of them also went by themselves to Spain. The volunteers were under no contract, nor defined engagement period, which would later prove a problem.

Also many Italians, Germans, and people from other countries with repressive governments joined the movement, with the idea that combat in Spain was a first step to restore democracy or advance a revolutionary cause in their own country. There were also many unemployed workers (especially from France), and adventurers. Finally, some 500 communists who had been exiled to Russia were sent to Spain (among them, experienced military leaders from the First World War like "Kléber" Stern, "Gomez" Zaisser, "Lukacs" Zalka and "Gal" Galicz, who would prove invaluable in combat).

The operation was met by communists with enthusiasm, but by anarchists with skepticism, at best. At first, the anarchists who controlled the borders with France were told to refuse communist volunteers, and reluctantly allowed their passage after protests. A group of 500 volunteers (mainly French, with a few exiled Poles and Germans) arrived in Albacete on 14 October 1936. They were met by international volunteers who had already been fighting in Spain: Germans from the Thälmann Battalion, Italians from Centuria Gastone Sozzi and French from Commune de Paris Battalion. Among them was British poet John Cornford. Men were sorted according to their experience and origin, and dispatched to units.

Albacete soon became the International Brigades headquarters and its main depot. It was run by a troika of Comintern heavyweights: André Marty was commander; Luigi Longo (Gallo) was Inspector-General; and Giuseppe Di Vittorio (Nicoletti) was chief political commissar.[3]

The French Communist Party provided uniforms for the Brigades. Discipline was extreme. For several weeks, the Brigades were locked in their base while their strict military training was under way.

Service

First engagements: Siege of Madrid

The Battle of Madrid was a major success for the Republic. It staved off the prospect of a rapid defeat at the hands of Francisco Franco's forces. The role of the International Brigades in this victory was generally recognised, but was exaggerated by Comintern propaganda, so that the outside world heard only of their victories, and not those of Spanish units. So successful was such propaganda that the British Ambassador, Sir Henry Chilton, declared that there were no Spaniards in the army which had defended Madrid. The International Brigade forces that fought in Madrid arrived after other successful Republican fighting. Of the 40,000 Republican troops in the city, the foreign troops numbered less than 3,000.[4] Even though the International Brigades did not win the battle by themselves, nor significantly change the situation, they certainly did provide an example by their determined fighting, and improved the morale of the population by demonstrating the concern of other nations in the fight. Many of the older members of the International Brigades provided valuable combat experience having fought during the First World War (Spain remained neutral in 1914-18) and the Irish War of Independence (Some fought in the IRA while others fought in the British army).

One of the strategic positions in Madrid was the Casa de Campo. There the Nationalist troops were Moroccans, commanded by General José Enrique Varela. They were excellent fighters in the open, but were ill-trained for urban warfare, a role in which the Republican militia had shown prowess in from the early days of the war. They were stopped by III and IV Brigades of the regular Republican Army.

On 9 November 1936, the XI International Brigade - comprising 1,900 men from the Edgar André Battalion, the Commune de Paris Battalion and the Dabrowski Battalion, together with a British machine-gun company - took up position at the Casa de Campo. In the evening, its commander, General Kléber, launched an assault on the Nationalist positions. This lasted for the whole night and part of the next morning. At the end of the fight, the Nationalist troops had been forced to retreat, abandoning all hopes of a direct assault on Madrid by Casa de Campo, while the XIth Brigade had lost a third of its personnel.

On 13 November, the 1,550-man strong XII International Brigade, made up of the Thälmann Battalion, the Garibaldi Battalion and the André Marty Battalion, deployed. Commanded by General "Lukacs", they assaulted Nationalist positions on the high ground of Cerro de los Angeles. As a result of language and communication problems, command issues, lack of rest, poor coordination with armoured units, and insufficient artillery support, the attack failed.

On November 19, the anarchist militias were forced to retreat, and Nationalist troops — Moroccans and Spanish Foreign Legionnaires, covered by the Nazi Condor Legion — captured a foothold in the University City. The 11th Brigade was sent to drive the Nationalists out of the University City. The battle was extremely bloody, a mix of artillery and aerial bombardment, with bayonet and grenade fights, room by room. Anarchist leader Buenaventura Durruti was shot there on 19 November 1936, and died the next day. The battle in the University went on until three quarters of the University City was under Nationalist control. Both sides then started setting up trenches and fortifications. It was then clear that any assault from either side would be far too costly; the nationalist leaders had to renounce the idea of a direct assault on Madrid, and prepare for a siege of the capital.

On 13 December 1936, 18,000 nationalist troops attempted an attack to close the encirclement of Madrid at Guadarrama — an engagement known as the Battle of the Corunna Road. The Republicans sent in a Soviet armoured unit, under General Dmitry Pavlov, and both XI and XII International Brigades. Violent combat followed, and they stopped the Nationalist advance.

An attack was then launched by the Republic on the Cordoba front. The battle ended in a form of stalemate; a communique was issued, saying: "[t]oday, our advance continued without loss of land". Poets Ralph Winston Fox and John Cornford were killed. Eventually, the Nationalists advanced, taking the hydro electric station at El Campo. André Marty accused the commander of the Marseillaise Battalion, Gaston Delasalle, of espionage and treason and had him executed. (It is doubtful that Delasalle would have been a spy for Francisco Franco; he was denounced by his own second-in-command, André Heussler, who was subsequently executed for treason during World War II by the French Resistance.)

Further Nationalist attempts after Christmas to encircle Madrid met with failure, but not without extremely violent combat. On 6 January 1937, the Thälmann Battalion arrived at Las Rozas, and held its positions until it was destroyed as a fighting force. On January 9, only 10 km had been lost to the Nationalists, when the XIII International Brigade and XIV International Brigade and the 1st British Company, arrived in Madrid. Violent Republican assaults were launched in attempt to retake the land, with little success. On January 15, trenches and fortifications were built by both sides, resulting in a stalemate.

The Nationalists did not take Madrid until the very end of the war, in March 1939. There were also some pockets of resistance during the consecutive months.

Battle of Jarama

On 6 February 1937, following the fall of Málaga, the nationalists launched an attack on the Madrid-Andalusia road, south of Madrid. The Nationalists quickly advanced on the little town Ciempozuelos, held by the XV International Brigade, which was composed of the British Battalion (British Commonwealth and Irish), the Dimitrov Battalion (miscellaneous Balkan nationalities), the 6 Février Battalion (Belgians and French), the Canadian Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion and the Abraham Lincoln Battalion (Americans, including African-American). An independent 80-men-strong (mainly) Irish unit, known as the Connolly Column, made up of people from both sides of the Irish border also fought. Several histories of the Irish in Spain record that they included an ex-Catholic Christian Brother and an ordained Church of Ireland (Anglican Protestant) Clergyman, fighting and dying on the same side. (These battalions were not composed entirely of one nationality or another, rather they were for the most part a mix of many)

On 11 February 1937, a Nationalist brigade launched a surprise attack on the André Marty Battalion (XIV International Brigade), stabbing its sentries and crossing the Jarama. The Garibaldi Battalion stopped the advance with heavy fire. At another point, the same tactic allowed the Nationalists to move their troops across the river.

On 12 February, the British Battalion, XV International Brigade took the brunt of the attack, remaining under heavy fire for seven hours. The position became known as "Suicide Hill". At the end of the day, only 225 of the 600 members of the British battalion remained. One company was captured by ruse, when Nationalists advanced among their ranks singing The Internationale.

On 17 February, the Republican Army counter-attacked. On February 23 and 27, the International Brigades were engaged, but with little success. The Lincoln Battalion was put under great pressure, with no artillery support. It suffered 120 killed and 175 wounded. Amongst the dead was the Irish poet Charles Donnelly.[5]

There were heavy casualties on both sides, and although "both claimed victory ... both suffered defeats".[6]. It resulted in a stalemate, with both sides digging in, creating elaborate trench systems.

On 22 February 1937 the League of Nations Non-Intervention Committee ban on foreign volunteers went into effect.

Battle of Guadalajara

After the failed assault on the Jarama, the Nationalists attempted another assault on Madrid, from the North-East this time. The objective was the town of Guadalajara, 50 km from Madrid. The whole Italian expeditionary corps — 35,000 men, with 80 battle tanks and 200 field artillery — was deployed, as Benito Mussolini wanted the victory to be credited to Italy. On 9 March 1937, the Italians made a breach in the Republican lines, but did not properly exploit the advance. However, the rest of the Nationalist army was advancing, and the situation appeared critical for the Republicans. A formation drawn from the best available units of the Republican army, including the XI and XII International Brigades, was quickly assembled.

At dawn on 10 March, the Nationalists closed in, and by noon, the Garibaldi Battalion counterattacked. Some confusion arose from the fact that the sides were not aware of each other's movements, and that both sides spoke Italian; this resulted in scouts from both sides exchanging information without realising they were enemies.[7] The Republican lines advanced and made contact with XI International Brigade. Fascist tanks were shot at and infantry patrols came into action. There was reportedly an incident in which a fascist officer asked why Italian soldiers were shooting at his party, and they responded Noi siamo Italiani di Garibaldi (literally: "we are Garibaldi Italian"), at which point the Fascists surrendered. The common language was used to advantage by the Republicans, who used loudspeakers and dropped leaflets from planes, to broadcast propaganda messages, including a promise to pay Fascist deserters.

On March 11, the Fascists broke the front of the Republican army. The Thälmann Battalion suffered heavy losses, but succeeded in holding the Trijueque-Torija road. The Garibaldi also held its positions. On March 12, Republican planes and tanks attacked. The Thälmann Battalion attacked Trijuete in a bayonet charge and re-took the town, capturing numerous prisoners.

The International Brigades also saw combat in the Battle of Teruel in January 1938. The 35th International Division suffered heavily in this battle from aerial bombardment as well as shortages of food, winter clothing and ammunition. The XIV International Brigade fought in the Battle of Ebro in July 1938, the last Republican offensive of the war.

Disbandment

The International Brigades were disbanded by the Republican government of Juan Negrín, who announced the decision in the League of Nations on 21 September 1938 in an effort to get the Nationalist's foreign backers to withdraw their troops and to persuade the western democracies such as France and Britain to end their arms embargo on the Republic. By this time there were about an estimated 10,000 foreign volunteers still serving in Spain for the Republican side, and about 50,000 foreign conscripts for the Nationalists (excluding another 30,000 Moroccans).[8]

Perhaps half of the International Bridgadists came from Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy or other countries, such as Hungary, which had authoritarian right-wing governments at the time. These men could not safely return home and parts of them were instead given honorary Spanish citizenship and integrated in to Spanish units of the Popular Army. The remainder were repatriated to their own countries. The Belgian volunteers lost their citizenship because they had served in a foreign army.[9]

Composition

Overview

-

- For a military overview, see International Brigades order of battle

The first brigades were composed mostly of French, Belgian, Italian, and German volunteers, backed by a sizeable contingent of Polish miners from Northern France and Belgium. The XIth, XIIth and XIIIth were the first brigades formed. Later, the XIVth and XVth Brigades were raised, mixing experienced soldiers with new volunteers. Smaller Brigades - the 86th, 129th and 150th - were formed in late 1937 and 1938, mostly for temporary tactical reasons.

About 32,000 [1] people volunteered to defend the Spanish Republic. Many were veterans of World War I. Their early engagements in 1936 during the Siege of Madrid amply demonstrated their military and propaganda value.

The international volunteers were mainly socialists, communists, or under communist authority, and a high proportion were Jewish. Some were involved in the fighting in Barcelona against Republican opponents of the Communists: the POUM (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, an anti-Stalinist Marxist party) and anarchists. These more libertarian groups like the POUM fought together on the front with the anarchist federations of the CNT (CNT, Confederación Nacional del Trabajo) and the FAI (FAI, Iberian Anarchist Federation) who had large support in the area of Catalonia. However, overseas volunteers from anarchist, socialist, liberal and other political positions also served with the international brigades.

To simplify communication, the battalions usually concentrated people of the same nationality or language group. The battalions were often (formally, at least) named after inspirational people or events. From Spring 1937 onwards, many battalions contained one Spanish volunteer company (about 150 men).

Later in the war, military discipline tightened and learning Spanish became mandatory. By decree of 23 September 1937, the International Brigades formally became units of the Spanish Foreign Legion[10]. This made them subject to the Spanish Code of Military Justice. However the Spanish Foreign Legion itself sided with the Nationalists throughout the coup and the civil war [11]. The same decree also specified that non-Spanish officers in the Brigades should not exceed Spanish ones by more than 50 per cent[12]

Data

See also:International Brigades data

|

Brigades' composition by nationality

|

Casualties

|

Non-Spanish battalions

- Abraham Lincoln Battalion: from the United States, Canada and Irish Free State, with some British, Cypriots and Chilean who lived in New York and were members of the Chilean worker club of New York.

- Connolly Column: This mostly Irish republican group fought as a section of the Lincoln Battalion

- Mickiewicz Battalion: predominantly Polish.

- André Marty Battalion: predominantly French and Belgian, named after André Marty.

- British Battalion: Mainly British but with many from the Irish Free State, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Cyprus and other Commonwealth countries.

- Checo-Balcánico Battalion: Czechoslovakian and Balkan.

- Commune de Paris Battalion: predominantly French.

- Deba Blagoiev Battalion: predominantly Bulgarian, later merged into the Djakovic Battalion.

- Dimitrov Battalion: Greek, Yugoslavian, Bulgarian, Czechoslovakian, Hungarian and Romanian. Named after Georgi Dimitrov.

- Djuro Djakovic Battalion: Yugoslav, Bulgarian, anarchist, named after the former Yugoslav communist party secretary Đuro Đaković.

- Dabrowski Battalion: mostly Polish and Hungarian. Also Czechoslovakian, Ukrainian, Bulgarian and Palestinian Jews. See also Dąbrowszczacy.

- Edgar André Battalion: mostly German. Also Austrian, Yugoslavian, Bulgarian, Albanian, Romanian, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian and Dutch.

- Español Battalion: Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican, Chilean, Argentinian and Bolivian.

- Figlio Battalion: mostly Italian; later merged with the Garibaldi Battalion.

- Garibaldi Battalion: Raised as the Italoespañol Battalion and renamed. Mostly Italian and Spanish, but contained some Albanians.

- George Washington Battalion: the second U.S. battalion. Later merged with the Lincoln Battalion, to form the Lincoln-Washington Battalion.

- Hans Beimler Battalion: mostly German; later merged with the Thälmann Battalion.

- Henri Barbusse Battalion: predominantly French.

- Henri Vuilleman Battalion: predominantly French.

- Louise Michel Battalions: French-speaking, later merged with the Henri Vuillemin Battalion.

- Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion: the "Mac-Paps", predominantly Canadian.

- Marseillaise Battalion: predominantly French-commanded by George Nathan.

- Incorporated one separate British company.

- Palafox Battalion: Yugoslavian, Polish, Czechoslovakian, Hungarian, Jewish and French.

- Naftali Botwin Company: a Jewish unit formed within the Palafox Battalion in December 1937.

- Pierre Brachet Battalion: mostly French.

- Rakosi Battalion: mainly Hungarian, also Czechoslovakians, Ukrainians, Poles, Chinese, Mongolians and Palestinian Jews.

- Nine Nations Battalion (also known as the Sans nons and Neuf Nationalités: French, Belgian, Italian, German, Austrian, Dutch, Danish, Swiss and Polish.

- Six Février Battalion ("Sixth of February"): French, Belgian, Moroccan, Algerian, Libyan, Syrian, Iranian, Iraqi, Chinese, Japanese, Indian and Palestinian Jewish.

- Thälmann Battalion: predominantly German, named after German communist leader Ernst Thälmann.

- Tom Mann Centuria: A small, mostly British, group who operated as a section of the Thälmann Battalion.

- Thomas Masaryk Battalion: mostly Czechoslovakian.

- Tschapaiew Battalion: Ukrainian, Polish, Czechoslovakian, Bulgarian, Yugoslavian, Turkish, Italian, German, Austrian, Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Belgian, French, Greek, Albanian, Dutch, Swiss and Baltic.

- Vaillant-Couturier Battalion: French, Belgian, Czechoslovakian, Bulgarian, Swedish, Norwegian and Danish.

- Veinte Battalion: American, British, Italian, Yugoslavian and Bulgarian.

- Zwölfte Februar Battalion: mostly Austrian.

Status after the war

Since the Civil War was eventually won by the Nationalists, the Brigadiers were initially on the "wrong side" of history, especially since most of their home countries had a right-wing government (in France, for instance, the Popular Front was not in power any more).

However, since most of these countries found themselves at war with the very powers which had been supporting the nationalists, the Brigadists gained some prestige as the first guard of the democracies, having fought a prophetical combat. Retrospectively, it was clear that the war in Spain was as much a precursor of the Second World War as a Spanish civil war.

Some glory was therefore accredited to the volunteers (a great deal of the survivors also fought gallantly during World War II), but this soon faded in the fear that it would promote (by association) communism.

An exception is among groups to the left of the Communist Parties, for example anarchists. Among these groups the Brigades, or at least their leadership, are criticised for their alleged role in suppressing the Spanish Revolution. An example of a modern work which promotes this view is Ken Loach's film Land and Freedom. A well-known contemporary account of the Spanish Civil War which also takes this view is George Orwell's book Homage to Catalonia.

East Germany

After the Second World War, the German Democratic Republic found itself in need of a 'founding myth' going beyond the conquest of eastern Nazi Germany by the Red Army. The Spanish Civil War, and especially the role of the International Brigades, were considered ideal, and became a substantial part of East Germany's memorial rituals, because of the substantial numbers of German communists who had served in the brigades.[18]

Canada

Survivors of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion were often investigated by the RCMP and denied employment when they returned to Canada. Some were prevented from serving in the military during the Second World War due to so-called "political unreliability".

Switzerland

In Switzerland, public sympathy was high for the Republican cause, but the federal government banned all fundraising and recruiting activities a month after the start of the war so as to preserve Swiss neutrality.[15] Around 800 Swiss volunteers joined the International Brigades, among them a small number of women.[15] Sixty percent of Swiss volunteers identified as communists, while the others included socialists, anarchists and antifascists.[15]

Some 170 Swiss volunteers were killed in the war.[15] The survivors were tried by military courts upon their return to Switzerland for violating the criminal prohibition on foreign military service.[15][19] The courts pronounced 420 sentences which ranged from around two weeks to four years in prison, and often also stripped the convicts of their political rights. In the judgment of Swiss historian Mauro Cerutti, volunteers were punished more harshly in Switzerland than in any other democratic country.[15]

Motions to pardon the Swiss brigadists on the account that they fought for a just cause have been repeatedly introduced in the Swiss federal parliament. A first such proposal was defeated in 1939 on neutrality grounds.[15] In 2002, Parliament again rejected a pardon of the Swiss war volunteers, with a majority arguing that they did break a law that remains in effect to this day.[20] In March 2009, Parliament adopted a third bill of pardon, retroactively rehabilitating Swiss brigadists, only a handful of whom were still alive.[21]

United States

In the United States, the volunteers were labeled as "premature anti-fascists" by the FBI, denied promotion during service in the US military during World War II, and pursued by Congressional committees during the Red Scare.[22][23]

Recognition

Spain

On 26 January 1996, the Spanish government gave Spanish citizenship to the Brigadists. At the time, roughly 600 remained. At the end of 1938, Prime Minister Juan Negrín had promised Spanish citizenship to the Brigadists, a promise which he could not personally keep as the Republic had lost the war.

France

In 1996, Jacques Chirac, then French President, granted the former French members of the International Brigades the legal status of former service personnel ("anciens combattants") following the request of two French communist Members of Parliament, Lefort and Asensi, both children of volunteers. Before 1996, the same request was turned down several times including by François Mitterrand, the former Socialist President.

Monuments

|

|

|||

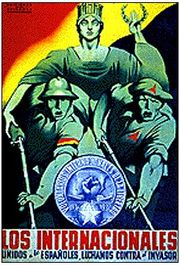

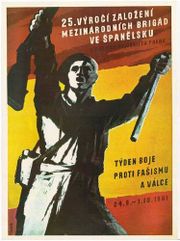

Symbolism and heraldry

The International Brigades were inheritors of a socialist aesthetic.

The flags featured the colours of the Spanish Republic : red, yellow and purple, often along with socialist symbols (red flags, hammer and sickle, fist). The emblem of the brigades themselves was the three-pointed red star, which is often featured.

Notable associated people

|

See also

- International Brigades order of battle

- International Brigade Memorial Trust

- Militant anti-fascism

- Abraham Lincoln Brigade

- Irish Socialist Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War

- Polish Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War

- Jewish Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War

- Arditi del Popolo

References and notes

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Thomas (2003), pp 941-3

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Spanish Civil War. p. 124. ISBN 0-911745-11-4

- ↑ Thomas (2003), 443

- ↑ Beevor. (1982) ‘’The Spanish Civil War’’, p 137; Anderson (2003) ‘’The Spanish Civil War: A History and Reference Guide’’, p 59.

- ↑ Archived April 4, 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Thomas (2003), 579

- ↑ Beevor. (1982) ‘’The Spanish Civil War’’, p 158.

- ↑ Exit - Time, Monday, 03 October 1938

- ↑ Orwell(1938) 'A Homage to Catalonia'

- ↑ Beevor (2006), p309.

- ↑ Beevor (2006), passim.

- ↑ (Spanish) Castells, Los Brigadas Internacionales, pp 258-9

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Thomas (1961), Appendix III

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 14.8 14.9 Marty attrib. S Álvarez

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 Daniele Mariani (February 27, 2008). "No pardon for Spanish civil war helpers". Swissinfo. http://www.swissinfo.org/eng/news/social_affairs/No_pardon_for_Spanish_civil_war_helpers.html?siteSect=201&sid=8751871.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Thomas (2001) p 574

- ↑ (1965) Hispaania tules. Mälestusi ja dokumente fašismivastasest võitlusest Hispaanias 1936.-1939. aastal. Editors: Olaf Kuuli, V.Riis, O.Utt. Tallinn: Eesti raamat.

- ↑ The Cult of the Spanish Civil War in East Germany (abstract) - Krammer, Arnold, Texas A&M University. Accessed 2008-05-14.)

- ↑ Swiss Military Penal Code , SR/RS 321.0 (E·D·F·I), art. 94 (E·D·F·I)

- ↑ Report of the Judicial Committee of the National Council, Off. J. 2002 pp. 7786 et seq.

- ↑ "Parliament pardons Spanish Civil War fighters". Swissinfo. http://www.swissinfo.org/eng/news_digest/Parliament_pardons_Spanish_Civil_War_fighters.html?siteSect=104&sid=10442150. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ↑ Premature antifascists and the Post-war world, Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives - Bill Susman Lecture Series. King Juan Carlos I of Spain Center at New York University, 1998. Accessed 2009-08-09.

- ↑ Premature Anti-Fascist, Bill Knox, reprinted from The Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives - Bill Susman Lecture Series. King Juan Carlos I of Spain Center - New York University, 1998. Accessed 2009-08-09.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/1999/04/08/classified/paid-notice-deaths-lidz-harry-h.html?pagewanted=1

Further reading and media

Nonfiction

- Alexander, Bill. British Volunteers For Liberty

- Baxell, Richard. British Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, Routledge, 2004

- Beevor, Antony . The Battle for Spain, 2006, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2006. ISBN 978-0297848325

- Fisher, Harry. Comrades: Tales of a Brigadista in the Spanish Civil War University of Nebraska Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8032-6899-8

- Grey, Daniel. Homage to Caledonia

- Lee, Laurie. A Moment of War, ISBN 978-0140156225

- Marty, André. Historia Política y Militar de las Brigadas Internacionales

- Monks, Joe. With the Reds in Andalusia

- O'Riordan, Michael. Connolly Column, Dublin, New Books, 1979

- Orwell, George. Homage to Catalonia

- Rust, Bill. Britons in Spain

- Ryan, Frank, editor. Book of the 15th Brigade, Madrid, Commissariat of War, 1938.

- Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War, 4th Rev Ed, 2003. ISBN 978-0141011615

Fiction

- Hemingway, Ernest. For Whom the Bell Tolls.

- Mitford, Nancy. The Pursuit of Love.

- Sansom, C. J. Winter in Madrid.

- Weiss, Peter. The Aesthetics of Resistance.

Photographs

Films

- Land and Freedom, by Ken Loach. Although the subject of the film is not the International Brigades, it portrays international volunteers in the Spanish Civil War. The actual International Brigades are featured.

- Sierra de Teruel by André Malraux, features the International bomber squadron in margin of the Brigades

- For Whom the Bell Tolls - 1943 film by Ernest Hemingway about a young American who fights in the International Brigades.

- Memories of a Future - 2007 film by Margaret Dickinson and Pepe Petos. This documentary follows a group of volunteers of the International Brigades, their friends and family travelling back to Figueres Spain in 2006. The film interrogates the relevance of the veteran's deed and contextualises it in current social and political climate.

- To My Son In Spain: Finnish Canadians in the Spanish Civil War, by Dave Clement, Kelly Saxberg, Saku Pinta, Sonya Lacroix and Michelle Derosier (Thunderstone Pictures). This documentary features the story of Jules Paivio, one of the last living Canadian volunteers of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion of the International Brigades.

External links

Websites

- British International Brigade veterans tell their stories - The Guardian

- 300 German and Austrian brigadists in French Internment camps search the various internment database

- Irish site on the SCW

- Webpages on the Irish IB members

- IBMT the international brigade memorial trust

- Farewell to the International Brigades

- Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives

- Spartacus Educational

- The International Brigades (Veterans' Stories)

- Ireland and the Spanish Civil War

- Reproduction of International Brigades flags, badges and t-shirts

- Freedom fighters or Comintern army? The International Brigades in Spain by Andy Durgan

- Pat Read - an Irish Anarchist in the SCW.

Audio streams

- [1] Martha Gellhorn talks about the Spanish Civil War (BBC Radio 4 audio stream).

- The Spanish Civil War - causes and legacy part of the BBC Radio 4 In Our Time series.

- PODCAST: Prof. Helen Graham - Border Crossings:Thinking about the International Brigades before and after Spain